Sequence Samples¶

This section describes the massively parallel sequencing pipeline. We first detail methods for sample procurement and nucleic acid extraction. Subsequently we provide an overview of library preparation, target enrichment, and next-generation sequencing (NGS). We also touch on new methods for NGS, which includes describing PacBio and NanoPore Sequencing. This high-level overview gives brief insight into how we employ custom capture reagents on tumor samples to enrich for variants of interest. Note, there are many variations of the following sequencing pipeline that may be appropriate for the individual researcher or clinical use case. This section is meant to provide a general overview of a typical pipeline.

Sample procurement¶

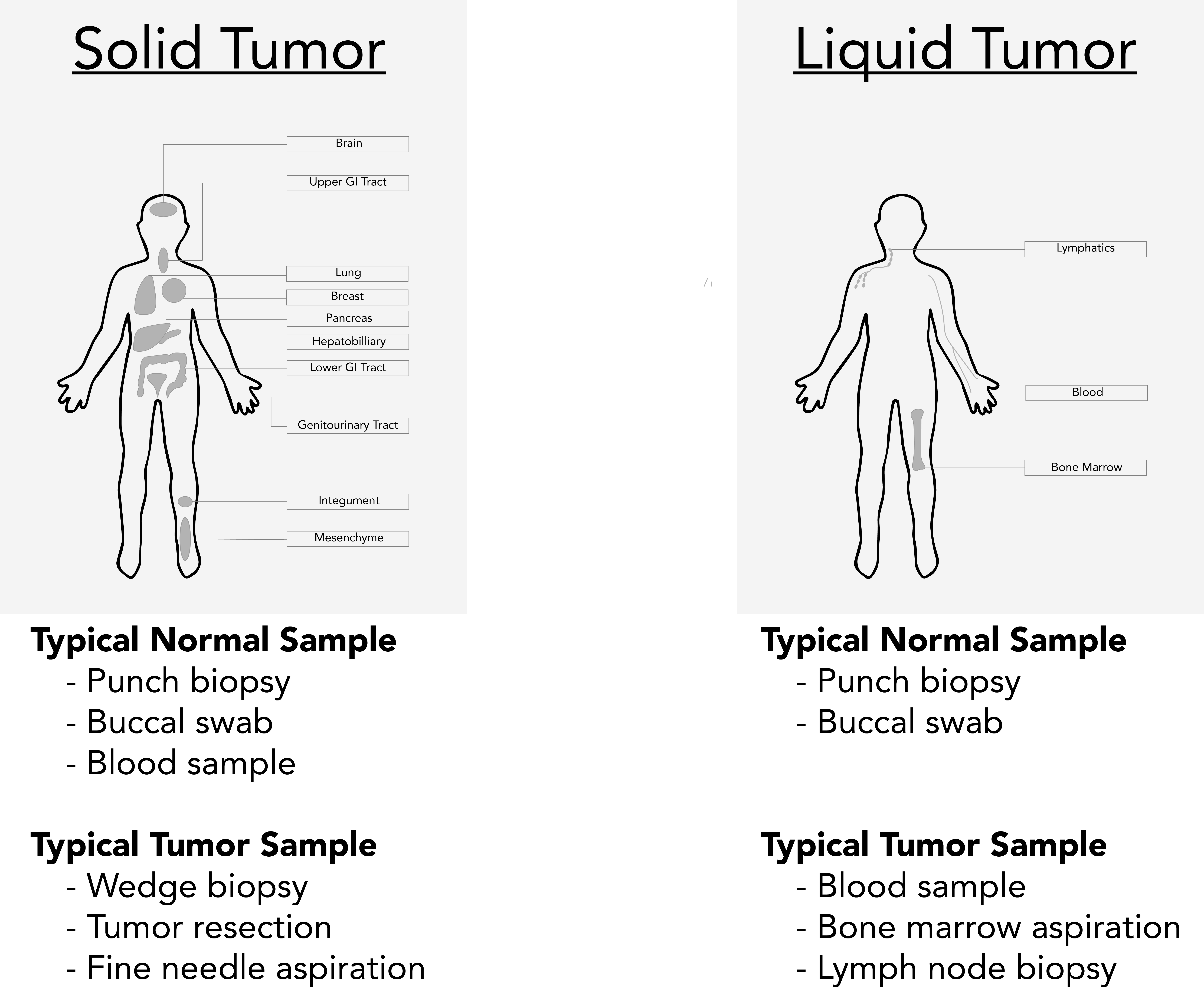

For the analysis described here, samples must be derived from a germline tissue (normal sample) and a diseased tissue (tumor sample). Procuring samples from these two sample types requires consideration of the malignancy:

- Liquid Cancers: A cancer that begins in blood-forming tissue, such as the bone marrow, or in the cells of the immune system (e.g., leukemia, multiple myeloma, and some lymphomas)

- Solid Cancers: An abnormal mass that does not contain cysts or liquid areas (e.g., sarcomas, carcinomas, and some lymphomas)

It is important to note that blood samples may not be suitable as the normal samples for solid cancers if the tumor is metastatic with high circulating tumor cells or circulating tumor DNA. In these cases, buccal swabs or skin biopsies may be better for tumor-normal comparisons.

Sample storage¶

Once samples are procured, they are typically preserved as fresh-frozen (FF) or formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) specimens.

- Fresh Frozen: As soon as samples are obtained, fresh frozen preparation requires exposing the sample to liquid nitrogen as quickly as possible. Samples must subsequently be stored in −80°C freezers until extraction.

- Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded: FFPE samples can be prepared using a variety of available kits (e.g., QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit, MagMAX™ FFPE DNA/RNA Ultra Kit, Quick-DNA/RNA FFPE Miniprep Kit, etc.).

Nucleic acid generation¶

If samples are stored as FFPE blocks, they require FFPE DNA extraction. This can be accomplished using commercially available kits. In general, these kits require paraffin removal and tissue rehydration, tissue digestion, mild reversal of cross-linkage, and nucleic acid purification. If samples are stored as fresh-frozen tissue blocks, they only require nucleic acid purification.

Nucleic acid purification requires cell lysis, binding of nucleic acid, washing off non nucleic acid material, drying of nucleic acid, and elution into a buffer. There are many commercially available kits that can perform nucleic acid purification. These steps can also be automated using commercially available equipment (e.g., QIAsymphony® SP, NUCLISENS® easyMAG®, etc.). Below we describe each step in detail:

Lyse: Tissue samples are typically stored as whole cells. The lysis step is used to disrupt the cellular membrane to expose the nucleic acid. Lysis buffers typically comprises a chaotropic agent, which breaks the hydrogen bond network between water molecules and optionally a surfactant to lower surface tension between membrane components and nucleic acid-containing solution. Some chaotropic agents can include: guanidium thiocyanate or magnesium chloride. Some surfactants can include: Triton-X-100, or sodium dodecyl sulfate.

Bind: After nucleic acid has been suspended in solution, it can be reversibly bound to a positively charged material for purification. These materials can include magnetic particles, columns, filters, silica beads, or organic solvent-based methods.

Wash: Once the nucleic acid is bound to a positively charged material, remaining substances in the lysate are washed from solution. A washing solution does not disrupt the covalent bond between the nucleic acid and the positively charged material used for purification.

Dry: To ensure proper elution, bound nucleic acid typically needs to be completely devoid of all liquid. To avoid degradation, alcohols can be used to expedite the drying step.

Elute: Elution buffers are solvents that displace the nucleic acid from the positively charged material used for purification. Elution buffers can include: 10 mM Tris at pH 8-9, Warmed MilliQ (60 oC), or 1X TE.

Cleanup: Elutions can be optionally treated with either RNAse (RNase ONE™ Ribonuclease, RNase A, etc.) or DNAse (e.g., DNase I <https://www.neb.com/protocols/0001/01/01/a-typical-dnase-i-reaction-protocol-m0303>, Baseline-ZERO™ DNase, etc.) to eliminate nucleic acid that is not being used in downstream analysis.

Quality check: After the nucleic acid generation step, it is recommended to assess the quantity and quality of the final elution. This can be accomplished using spectrophotometry and/or electropherograms.

- Spectrophotometry measures a substance’s ability to absorb a specific wavelength, which in turn is a proxy for concentration and purity. First, the sample is exposed to an ultraviolet light at a wavelength of 260 nanometres (nm) and the DNA and RNA in the sample will absorb a relative amount of the light that is proportional to the concentration. Next a photo-detector measures the light that passes through the sample (i.e., not absorbed), which allows you to calculate the quantification of DNA/RNA in the sample. Nucleic acid quantification using spectrophotometry relies on the Beer–Lambert law.

- Electropherograms measure the nucleic acid concentration and size using a fluorescent spectrum. The Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer evaluates the sample using a spectrum of fluorescents. The Qubit 4 Fluorometer utilizes fluorescent dyes that are specific to the target of interest.

Library construction¶

In advance of next-generation sequencing (NGS), construction of sequencing libraries is first required. This typically requires genomic fragmentation, ligation to custom linkers called adapters, and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification.

- Genome fragmentation involves breaking the DNA into smaller pieces using physical or chemical means.

- Physical fragmentation methods include sonication, nebulization or enzymatic reactions.

- Chemical fragmentation relies on hydroxyl radicals to break DNA into fragments, which can accommodate more material, but can induce false positives through novel mutations or transversion artifacts.

- Adaptors are chemically synthesized double stranded DNA molecules that make sequencing reactions possible. Adaptors are ligated to DNA fragments and may include sequences to allow binding to a flowcell, sequencing primer sites, sample indexes, unique molecular identifier (UMI) sequences, etc.

- PCR amplification is a method to make many copies of a specific DNA segment. PCR requires first denaturing dsDNA to create ssDNA using heat, binding of targeted primers to ssDNA fragments, and elongation of ssDNA to create a copied dsDNA. Amplification is typically performed at multiple steps in the sequencing pipeline.

Target enrichment strategies¶

Target enrichment strategies are used to generate a specific collection of DNA fragments for sequencing. These enrichment strategies are often performed on the constructed sequence library or incorporated into a library construction step.

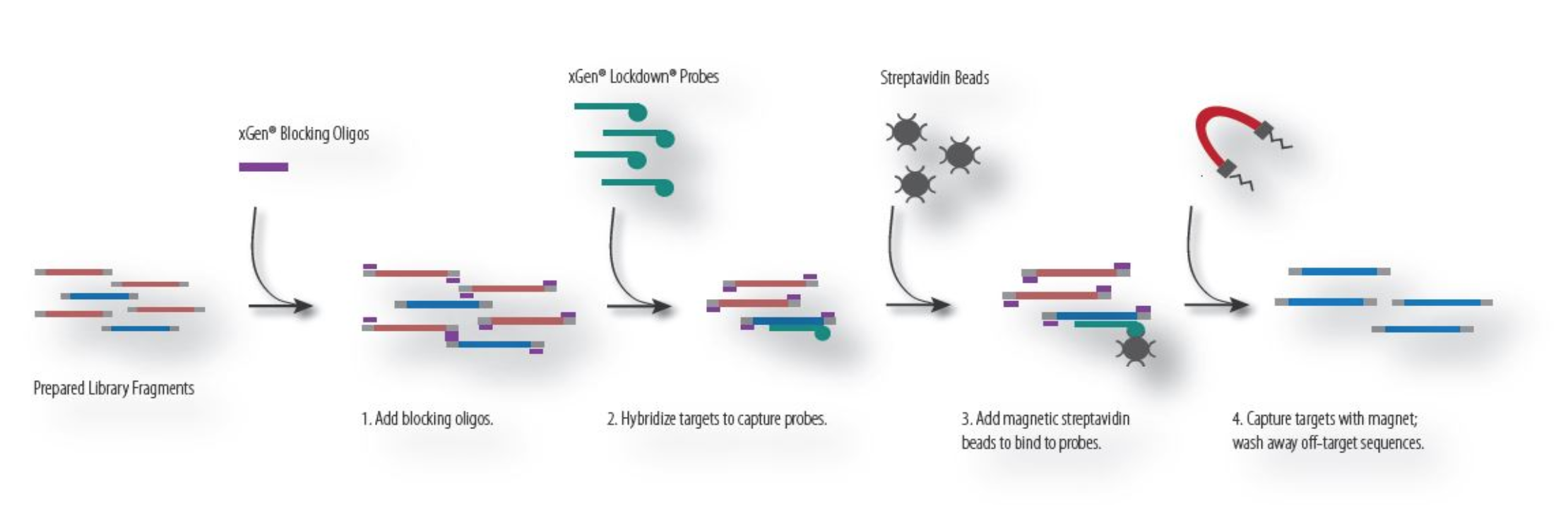

Hybridization Capture¶

Hybridization capture requires designing specific primers that bind to regions of interest and isolating these bound DNA fragments using chemistry (e.g., use of strepavidin Beads in combination with biotinylated DNA). Genomic DNA that is not bound to the capture probes will be washed away. The remaining DNA, which is enriched for regions of interest, is amplified using PCR and sequenced. Reagents that use hybridization capture include: Swift BioSciences, IDT, Agilent, among others. The process for hybridization capture is described below:

Amplicon Enrichment¶

Amplicon enrichment uses a slightly different strategy for enrichment of regions of interest. Instead of hybridization based capture, regions of interest are amplified by PCR using sets of primer sequences designed to target regions of interest. Reagents that use amplicon sequencing include: QIAGEN, Illumina, and others. An example of the process of amplicon enrichment is shown below:

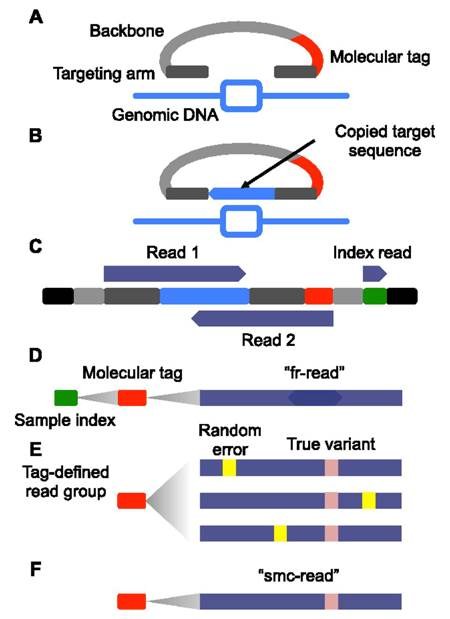

Unique Molecular Identifiers¶

Unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) are short sequences or molecular tags that can be added to each read during library preparation. Typically, these molecular identifiers are added prior to amplification so that they tag individual DNA molecules observed in the sample. This allows the individual to assign all amplification products to a single originating DNA molecule after sequencing. Through a process of consensus read formation, individual sequencing-related errors can be discounted, decreasing the effective error-rate of sequencing. UMI-based sequencing can take on many forms, each unique to the individual library preparation. An example of the single molecule molecular inversion probe approach is provided below:

Other considerations¶

Of note, for evaluation of RNA, total RNA must be subjected to reverse transcriptase treatment (e.g., ProtoScript® II Reverse Transcriptase, SuperScript™ III Reverse Transcriptase) to generate cDNA prior to library preparation.

High throughput sequencing¶

Next-generation sequencing¶

Sequencing is the final step in data production part of a genomic analysis pipeline. The most commonly used sequencing technique is so-called next-generation sequencing (NGS) or high-throughput sequencing, which evaluates millions of sequences in parallel to dramatically reduce time and cost of the analysis. There are at least two popular platforms (in use clinically) that harness the power of next-generation sequencing to efficiently sequence tumor samples:

- Illumina sequencing anneals individual reads to a bead or plate using DNA adaptors and the molecule is amplified through PCR. Amplified reads are sequenced by individually adding single fluorescently tagged and blocked-nucleotides to the complementary DNA sequence and exposing the nucleotide to light to produce a characteristic fluorescence. These blocked-nucleotides can then be un-blocked to allow for an additional base to bind and the process repeated until the whole complementary sequence is elucidated. This platform has a high accuracy rate and can evaluate 50-300 base-pairs per read, and very high-throughput runs producing millions to billions of reads. Each run takes approximately 2-3 days to complete for as little as $1,000 per 30x whole genome sample.

- ThermoFisher ION Torrent evaluates hydrogen atoms emitted during polymerization of base pairs, which can be measured as a variation in the solution’s pH. This method has a low error rate for substitutions and point mutations and it is relatively inexpensive with a fast turn-around for data production (2-7 hours per run), however, the platform has higher error rates for insertions and deletions, it cannot read long chains of mononucleotides, and it cannot currently match the throughput of the Illumina sequencing platform.

Third generation sequencing¶

Third Generation Sequencing Platforms: PacBio and NanoPore are considered third generation sequencing technologies that can sequence longer reads at a reduced cost to address the existing problems associated with NGS.

- PacBio utilizes hairpin adaptors to create a loop of DNA that can be fed through an immobilized polymerase to add complementary base pairs. As each nucleotide is held in the detection volume by the polymerase, a light pulse identifies the base. This platform requires high quality intact DNA with highly controlled fragmentation and can read strands up to 1Mb in length.

- Oxford NanoPore Sequencing utilizes biological transmembrane proteins that translocalize DNA. Measurement of changes in electoral conductivity as the DNA passes through the pore elucidates sequence reads. This platform can evaluate variable length reads and is inexpensive relative to other technologies. Specifically, the MinION device is completely portable, commercially available and can evaluate 20-100MB per run. The tradeoff is its low fidelity rate of only ~85%.